If you are around horses long enough, eventually you will run into thrush. Thrush is a common anaerobic bacterial infection that typically affects the central sulcus (the groove in the middle of the frog) and/or collateral sulcus or commissures (the grooves on the sides of the frog).1-5 The degeneration of the frog is characterized by a black foul-smelling material. 1-5,8

The most common bacterium associated with Thrush is Spherophorus necrophorus (aka Fusobacterium necrophorum); however, other anaerobic (most suited to living in an environment with little to no oxygen) bacteria and fungi are also potential culprits.4-7 The F. necrophorum bacteria is found naturally in the soil and decaying feces. Because this microbe is anaerobic, it thrives in a moist, dark, poorly oxygenated enrironment.4-6

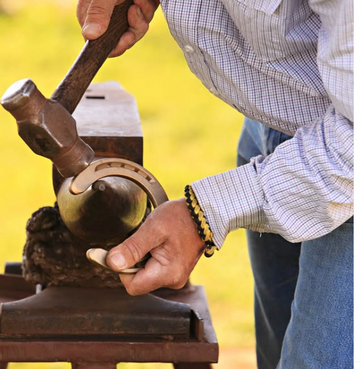

The foul smell that is created by Thrush is due to the microbes consuming the connective tissue proteins and sulfur and excreting a volatile compound as waste. Thrush is the odor of the sulfur being released by the microbes. The same smell occurs when hot shoeing. The odor produced is the smell of sulfur gas from the burning the sulfur rich connective tissue proteins of the hoof.8

Recognition of thrush is straightforward based on clinical signs such as black discharge, offensive foul-smelling odor, sensitivity and tenderness, bleeding, and frog degeneration or loss.1,2,4,5

Thrush is an opportunist, and it becomes a problem when blood supply, movement, hygiene, environment, diet, or hoof care are compromised. There are several factors that cause a horse to be susceptible to thrush. Some of these factors that contribute to the problem are: 1-6

Thrush can occur in any horse, so prevention becomes vital. Good thrush prevention includes regular hoof inspections, regular and correct trimming, exercising regularly, good stall and pasture management, good owner hygiene practices, and addressing any hoof and conformational issues.1-6

Once these factors have been successfully addressed, the next step is treatment. The first step is to trim away the dead infected tissue (usually done by your farrier or veterinarian).1,2,4,6

The second step is to thoroughly clean out the area with a soft brush and water or a dilute iodine solution.4,6

The third step involves a choice of a variety of thrush products, commercially and home made1,2,4-6,9,10 as well as applying EPA approved copper alloy horseshoes.11 Choosing the best thrush product comes down to your own preferences and recommendations. Most products require daily use. For best results, follow the product instructions. Application of topicals may come as a liquid, aerosol, or powder. Some remedies (bleach, hydrogen peroxide, turpentine, formaldehyde, motor oil, axel grease, pine tar, bacon grease, and copper sulfate) are not recommended by many veterinarians and farriers as these products can be ineffective, damage healthy tissue, and prolong healing time.4,9

Some recommended products are copper sulfate solution, 1,2 chlorine dioxide solutions, 1,2 crushed metronidazole tablet paste, 1,2,10 homemade remedies such as sugardine (a combination of sugar and betadine scrub), 4 commercially sold products, 5,10 tea tree oil,8,9 and EPA approved copper alloy horseshoes. 11

On more severe cases, work with your farrier and veterinarian to find a treatment solution that works for your horse. Prognosis for thrush is good in nearly all cases, especially if early and consistent treatment is applied.

References and Resources1. Belknap, J.K. (2016). Thrush in Horses. Rahway, NJ. Merck & Company, Inc. Retrieved from Thrush in Horses - Musculoskeletal System - Merck Veterinary Manual.pdf

2. Thrush. (1998). The Merck Veterinary Manual (8th Edition). page 822. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co, Inc.

3. Blood, DC; Studdert, VP; Gay, CC. Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary. (2007). (Third Edition). page 1796. Toronto, Canada: Elsevier.

4. Oke, S. (2016). Thrush in Horses – The Horse Fact Sheet. The Horse Media Group. Retrieved from thrush-in-horses-299771.pdf

5. Thrush. The Atlanta Equine Clinic, Hoschton, GA. Retrieved from AEC Client Education - Thrush.pdf

6. Dabareiner, R.M.; Moyer, W.; Carter, G.K. “Trauma to the sole and the wall.” In: Ross, M.W., Dyson, S.J., eds. Diagnosis and Management of Lameness in the Horse. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003:277

7. Petrov, K.K.; Dicks, L.M. (2013). Fusobacterium necrophorum, and not Dichelobacter nodosus, is associated with equine hoof thrush. Veterinary Microbiology. 2013 Jan 25;161(3-4):350-2. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.07.037. Epub 2012 Jul 27

8. What Creates the Foul Odor of Thrush? (2019). Life Data Labs, Inc. Retrieved from What Creates the Foul Odor of Thrush_ - Life Data® Blog.pdf

9. Debunking Hoof Remedies for Equine Thrush. (2018). Life Data Labs, Inc. Retrieved from debunking-hoof-remedie.pdf

10. Strait, AS, Bryk-Lucy, JA, Ritchie, LM. (2022). Evaluation of Effectiveness of Three Common Equine Thrush Treatments. International Journal of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, Vol:16, No:09, 2022.

11. Copper Alloy Horseshoes. Kawell USA, Chino, CA. Retrieved from Kawell USA - Naturally the Next Step